Amongst dream pop icons, Dexter Tortoriello doesn’t have the best voice (Dawn Golden is his solo side project). But I don’t think that’s the point: the music hear allows us to hear his voice bend to the notes of the surrounding instruments, making the music more surreal than it already is. It’s a trick that Radiohead has been using since OK Computer, and it works really well here. (Interestingly enough, Ozzy Osborn’s similar “technique” was what led Black Sabbath to their early success, so don’t discredit this for an unfortunate parlour trick — it’s really effective.)

If the point of dream pop is to take you somewhere surreal and seemingly unnatural, despite its largely organic roots, Still Life succeeds wildly. By using his voice as an instrument, Tortoriello is able to create something that succeeds for similar reasons Sylvan Esso’s debut does. Listen to I Won’t Bend — it’s a fantastic example of the way Tortoriello’s voice blends with the notes of the instruments around it. I also love Swing, Chevrotain, Still Life, and Discoloration.

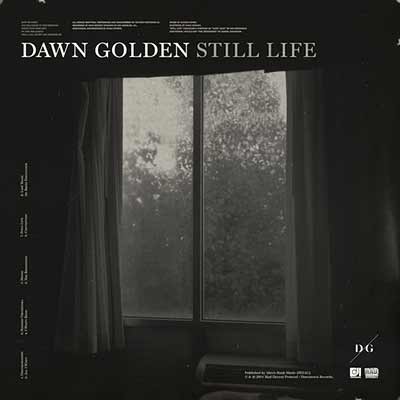

Reportedly, Still Life took three years to write. It’s a downcast record all the way through, personal and isolated, and as Tortoriello disappears into the electronics, it becomes more than a parlour trick. By the end of the record, the loss of voice is the album’s most obvious metaphor.