“Mike Douglas on the Moon with Amethyst” is where Tokyo-chutei-iki’s grand vision comes together and creates something altogether surprising and new, eight tracks into their absurdly entertaining and ridiculous jazz record.

The first minute and a half sounds nearly Hitchcockian, in a sort of terrifying way, where the all-saxophone jazz ensemble brings out all the discordant stops. The second half is the deconstruction of its first, where everything the first half completes is undone and left blowing in the wind, powerless after a single saxophone innocently renders it into fearless noise.

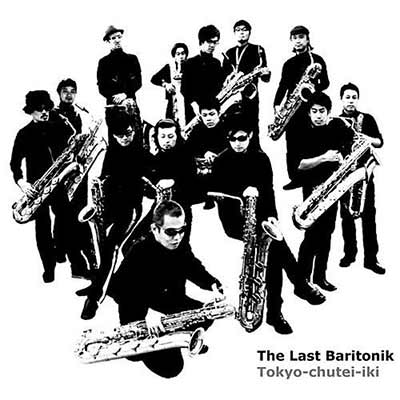

To put it simply, Tokyo-chutei-iki doesn’t care about what your preconceptions are about jazz. They forge their own paths on The Last Baritonik, with a playful nature that captures the improv the genre is known for. The band is made up of thirteen saxophone players (although I think they had ten at one point), with no other supporting elements.

The opening track is as joyful as jazz gets: “One Hundred Fingers” is a celebration of the genre, a cheerful burst of solos that’s the musical equivalent of a menagerie. It doesn’t take long to understand the fascination of what could easily be a novelty act: saxophones are both musical and rhythmic, capable of carrying a melody and a beat. And because they carry such a wide tone of sounds, saxophones are also easily able to be distinguishable from one another when the need occurs.

Saxophones also, of course, lend a visceral and playful nature to the music. “The Room of Iron Frame” dodges back and forth between noises that frighten and noises that play in an intoxicating mix that feels like multiple musical set pieces in a jazz opera. It’s thoroughly unconventional and surprising, never settling to be comfortable or comparable to anything we’re already intimately familiar with.

This level of ingenuity speaks to what makes Tokyo-chutei-iki so important to jazz as a genre right now: they might understand where the genre has been (and I’d argue their reliance on saxophones makes that clear), but their astute understanding of classical composition and disregard for jazz practice makes them more jazz-like than most of their contemporaries.

Jazz has shed its original clothing to become less married to specific time signatures or dances and more married to experimentation as art. And The Last Baritonik is definitely that. Tracks like “It is Soroso Spring”, complete with Japanese vocal work, feel like they belong in a post-modern opera.

When a single track is clearly influenced by Baroque-period classical, Miles Davis, and The Beatles, you know you’ve stumbled onto a sound that is inherently unique.

The Last Baritonik is a complete surprise and utterly imbibes jazz’s experimental soul. Tokyo-chutei-iki are, without a doubt, one of the genre’s most important flag-bearers right now.