In November, Pandora Radio announced they’d be acquiring Rdio. Rdio shut down within weeks, leaving a gaping hole in the music industry. It doesn’t matter why Rdio died, or who the company owed money to — ultimately, the saddest part of Rdio’s disappearance is what it leaves behind.

Rdio was the first online streaming service in the mobile era, arriving in 2010 and well before Spotify did. It sported what was a modern design (at the time), and was continually updated to look as good as possible.

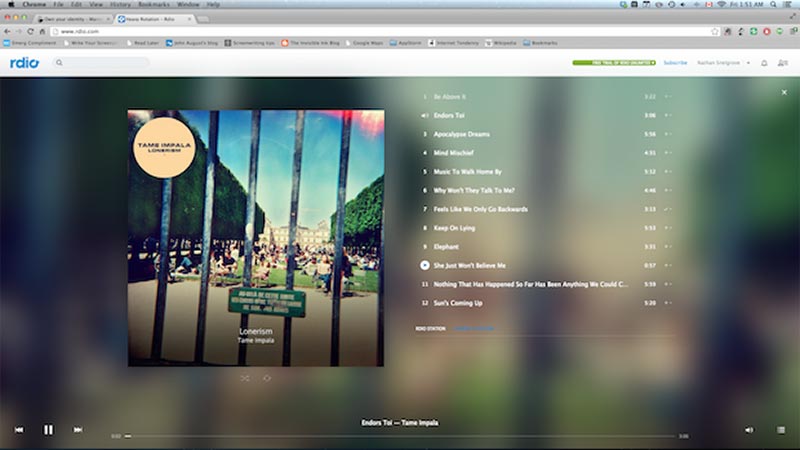

Strictly from a design standpoint, it can’t be understated that Rdio was one of the most gorgeous pieces of music software ever made. In fact, much of its design inspired the trends we have today in Windows 8 and 10 and iOS 7 and up. That flat look was very much an Rdio trademark.

More importantly, though, was Rdio’s attention to the people who used the service.

Rdio was competing — in its earliest days — with Deezer, MOG, Napster, and Rhapsody. About a year later, they started competing with Spotify as well. But Rdio was the only music app that understood how we talk about music.

A Place to Share Music with Friends

How many times have we chatted with friends and had them tell us about a great new record we should check out, only to forget about it later and never listen to it? That was the problem Rdio solved.

Many of Rdio’s contemporaries, like Spotify and Apple Music, use a mixture of human curation and machine algorithms to decide what to share with us. But Rdio allowed you to follow your friends and see what they were frequently playing, alongside the music that was topping the charts.

This mixture allowed for easy discovery: it became trivial to find new music your friends liked as well as listen to the day’s greatest hits. It nearly made Unsung Sundays unnecessary, actually. By very virtue of being perfectly-curated, it took social music to its most natural evolution.

To this day, I’ve never had better music recommendations than the ones I’ve received from Rdio. That’s largely because my friends, people who I trust to have great musical taste, were always listening to rad new music. But it’s also because I was in total control of it.

Didn’t like something, or found somebody’s tastes weren’t as aligned with mine as I thought? No problem; I could simply unfollow them and the problem was solved. As a point of comparison, Apple Music takes forever to notice what I like unless I specifically tell it so. But if I tell Apple Music that I like Kanye West, the app suddenly decides to constantly recommend Kanye West playlists and albums to me, despite the fact that I’m well aware of him and am more interested in finding something new.

On the other hand, Spotify nails it with their Discover Weekly service: 30 songs that feel hand-picked by a loving friend despite being served by a machine algorithm. People rightly (and justifiably) love it. But it feels cold and impersonal, much in the same way that those cutesy “Good afternoon!” messages Facebook occasionally shares with me in my timeline feel cold and impersonal. The machine is not my friend.

The best thing about these social recommendations, though, is that they avoided the echo chamber. They forced tastes to expand. They enabled people, through the comfort of their friends’ recommendations, to discover something new to them on a nearly-daily basis.

One of Rdio’s other joys was that they put the album first. Many purists will tell you that the best way to enjoy music is to put on a record and listen to it from first track to last, in the dark, with headphones on. This very website was founded on that belief. And Rdio’s design and system put records front and centre.

This was — and very much is — a unique combination that made Rdio the service to beat. It was highly-recommended and very well-reviewed, often considered the best streaming service by a mile. Beyond that, it had the potential to be culturally significant: music hadn’t felt that naturally social since the pre-iTunes days, when you had to physically go to a record store to buy the latest and greatest. Pair that with an obsession with the record instead of the single, and you had a service that seemed destined to change the way young people — tomorrow’s recording artists and trend-setters — look at music in its most popular forms.

All this was taken away from us when Rdio shut down.

I was part of the problem: like many other people, I switched to Apple Music in the summer when the service promised tighter integration with my iPhone. I started missing Rdio immediately, but the service was frequently becoming buggy and showed no sign of changing any time soon. Around the same time, my friends and I all stopped using the service.

Perhaps the biggest problem with software is its impermanence. Now, as I look at the landscape of music streaming services and think about what the offerings are today, I’m left with only one thought:

I miss Rdio.