If you’re like me, the first time you heard of Esperanza Spalding was when she became the first jazz musician to win Best New Artist at the Grammys in 2011, beating Justin Bieber to the claim and becoming something of a household name in the process. (I was thrilled; I’m not a Belieber and Spalding’s win was something I perceived to be good taste.) Her traditional jazz, upright bass and all, had somehow won over the voters and left her with a shiny new statuette.

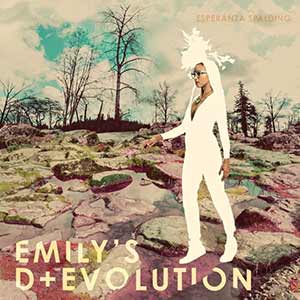

It seems that the fame got to her, in the way that sudden fame can seem suddenly alienating and confusing for many musicians. Emily’s D+Evolution feels like a direct response to that success, as Spalding runs in the opposite direction of much of what she was known for and chooses to grow by pushing jazz into unexpected, prog-rock like directions.

Good Lava and Judas both feel positively polyrhythmic, with unpredictable and jazzy guitar riffs guiding pummelling alt-rock tracks from beginning to end, and Spalding’s voice somehow uniting all of these wild elements together. The two tracks are great summaries of what you can expect from the rest of the album: although Spalding’s gone electric, her musicians are still playing jazz. Wild drums, virtuoso guitar parts, driving bass lines that completely ignore the main riff while tying the whole track together, time signatures that are difficult to predict and harder to understand, all these things are key components to the jazz experience.

This is an authentic jazz record, but it’s done with rock music. And while plenty of people have played jazz rock before, this feels like a rare time when it’s a jazz band becoming interested in rock music — not the other way around.

At the centre of it all is Emily, a character that Spalding recently told NPR came to her in a dream. And while she claims Emily, which is also Spalding’s middle name, isn’t some sort of Slim Shady-style Id being worked out through her Ego, it seems sort of obvious that’s the case in a lot of ways.

fHaving naturally taken chamber jazz as far as it could go, moving into alt-rock territory could be perceived as an evolution or de-evolution by Spalding’s audience. As a character, Emily is a way for Spalding to avoid taking the brunt of the weight that comes with criticism, a way for her to use an alter ego to explore something new without allowing it to hurt the goodwill she’s built up as a jazz performer — much the same way that Slim Shady allowed Eminem to become completely, publicly outrageous without ever necessarily being perceived as a total lunatic or real menace to society (at least, not by his fans).

All that being said, Emily feels more attuned to social justice and hippy love than Esperanza is. It’s not that Emily allows her to explore lyrical insanities, so much as Emily allows her to experiment with the form without sacrificing her jazz roots. She’s taking the form electric the same way that Dylan took folk rock electric — and it’s incredible.